The NUN’S GUIDE

“Con tutti voi!”

@nunsguide || Bishop’s Stortford

“We are one family, with one Father,

who makes the sun rise on everyone;

we inhabit the same planet and we

must care for it together”

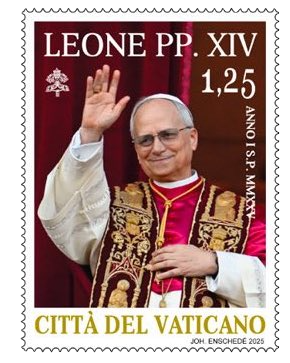

Papa Leone XIV

Shutterstock Alessia Pierdomenico

HEAVENLY CATHEDRALS

FINDING today’s BERNINI

SEMINARIANS on their CALLING

THRIVING MONASTERIES

Shutterstock © Riccardo De Luca

Homily in Saint Peter’s Basilica

Sunday 26th October 2025

The Church is the visible sign of the union between God and humanity… where God intends to bring us all together into one family of brothers and sisters, united in the embrace of his love. We are all children of God, called to serve one another. No one is called to dominate; we must listen to one another. No one is excluded; we are all called to participate. No one possesses the whole truth; we must humbly seek it together… the supreme rule in the Church is love.

“

1691

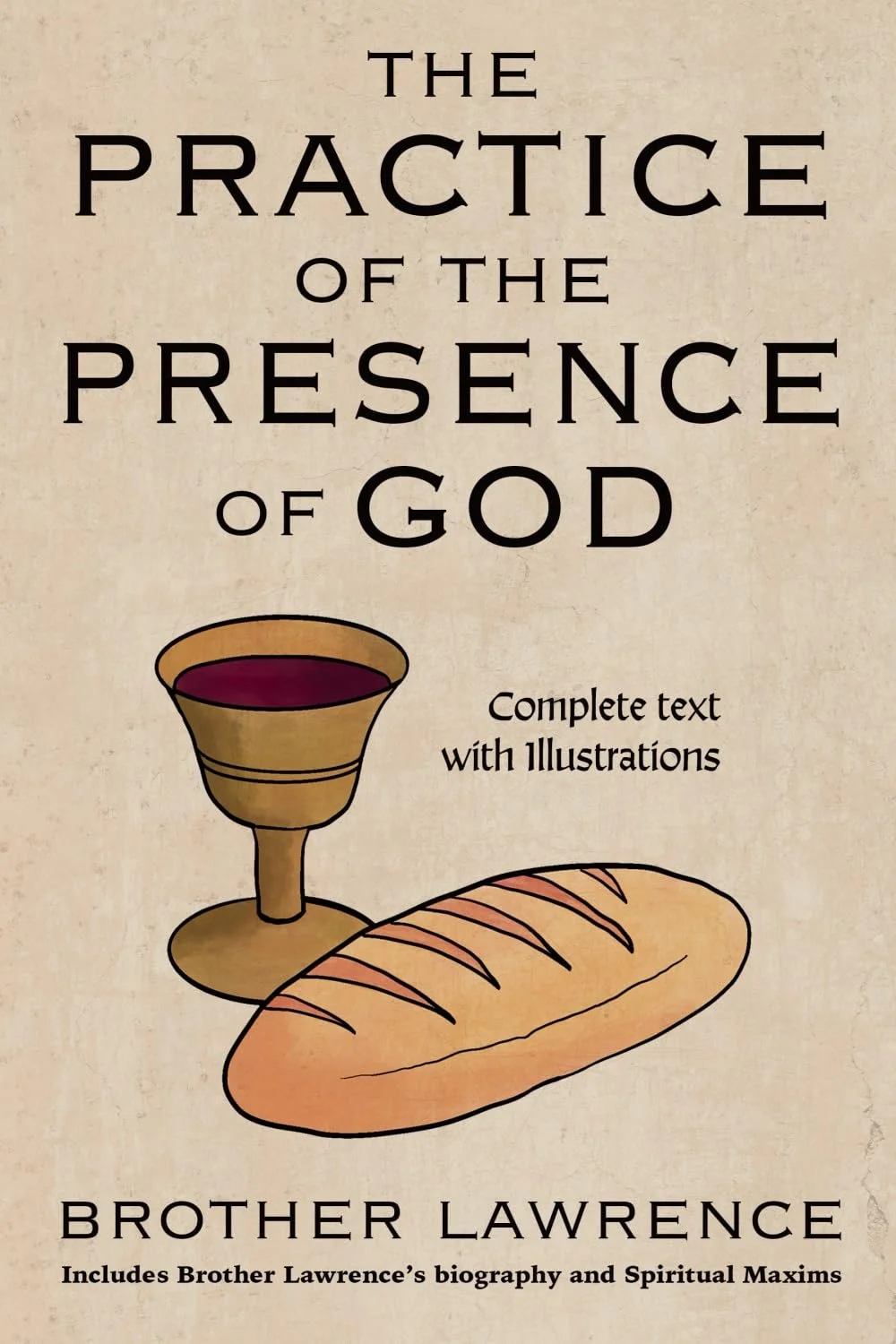

Aside from Saint Augustine, the book that has most shaped Pope Leo, turning a young American priest into our supreme pontiff, is a short collection of letters by a clumsy French soldier and footman who considered himself damned, so joined a barefoot monastery in Paris in 1666, expecting the severest discipline, only to find the Lord resting in the centre of his soul, filling him with tranquility and joys so continual, “I can scarce contain them.”

Having seen a tree stripped of its leaves on a battlefield in mid-winter, knowing its flowers would reappear, Brother Lawrence was resigned to giving-up pleasure, but also avoided formulaic prayers and devotions, making small personal appeals to God continually through the day (“My God, here I am, all devoted to Thee...”), building a deeply personal friendship, more intimate and casual than any conventional Catholic teaching.

In the clatter of the monastery kitchen, or rolling around in a boat in Burgundy, buying casks of wine for his brothers, the Lord in turn responded, conversing with Brother Lawrence incessantly “in a thousand and a thousand ways, and treats me in all respects as His favourite.”

Our thoughts rove and wander, but spiritual freedom need not be a hard struggle: God is as present to road-builders as priests serving at the altar and his love is like a current of water that we try to resist and hinder, but once we put our whole trust in the Lord and make a “total surrender”, believing beyond doubt in His mercy and “perfect goodness”, joy pours like a torrent that has “found its passage.”

Salus Populi Romani, Protectress of the Roman People, said to have been painted by Saint Luke; his Gospel has the greatest detail on Mary’s life, thought to be based on her own conversations, and the icon was restored by Pope Francis (1936-2025), who prayed before the painting before every journey and is buried in the same basilica, Santa Maria Maggiore, in a white tomb marked “FRANCISCVS”

Across the piazza, in Rome’s 15th Rione, the Santa Prassede basilica has some of the first Christian mosaics, dedicated to two daughters of a Roman senator, who became zealous converts after meeting Saint Peter

La METRO: Termini (Line A & B)

Vittorio Emanuele (Line A)

ROMA 27 Via Liberiana, Esquilino

France

Mont-Saint-Michel

Notre-Dame de Paris

Saint-Étienne de Toulouse

Sainte-Cecile d’Albi

Spain

San Juan de la Peña

Santiago de Compostela

Nuestra Señora del Pilar

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción

Basílica de la Encarnación

Sagrada Família

Rome

Piazza San Pietro

Santa Maria della Vittoria

Campo Santo dei Teutonici

Italy

Madonna di San Luca

San Francesco d’Assisi

Sant'Antonio di Padova

Chiesa di Gesù Nuovo

Duomo di Monreale

Duomo di Siracusa

2025

“Your gold and silver have rusted,” warns the Letter of James, “their rust will be evidence against you and it will eat your flesh like fire... Listen! The wages of the labourers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, cry out, and the cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord.”

This is the Bible’s call to those living in luxury and idle pleasure, according to Pope Leo’s first letter to the faithful, Dilexi Te. For Saint Ambrose (c.339 to 397), Bishop of Milan, charity was less a paternal gesture than justice restored. “Do not honour Christ’s body here in church with silk fabrics,” preached John Chrysostom (347 to 407), Archbishop of Constantinople, “while he himself dies of hunger in the person of the poor.”

Clare of Assisi (1194 to 1253) also chose barefooted poverty over papal privileges, teaching her sisters to recognise Christ as their only inheritance, letting nothing obscure their communion with him. From his birth in a humble manger, taken to the Temple with two turtledoves, the offering of the lowly, God lived on earth as an itinerant teacher, his poverty and precariousness a sign of his deep spiritual bond to his Father and trust in providence to the end.

Born in Chicago

14th September 1955

“Robert Francis Prevost”, born in the Mercy Hospital, Chicago. His father Louis was a US Navy veteran, whilst his mother Mildred sent the children to Mass before school every day, explaining that Jesus is “your best friend”

Ordained Priest

10th September 1981

Re-enacting Mass at home, “Rob” became an altar boy and always wanted to be a priest. Described by nuns as “calm and steady… a person at peace with himself”, he taught maths while studying Divinity and joined the Augustinians in Missouri, training for the priesthood

Prior of Seminary

1988 to 1998

Sent to Rome to study Canon Law, joining aid missions to Peru, leading its seminary in Trujillo for 10 years, travelling by mule to remote regions, finding Peruvians to join the priesthood

Leads Augustinians

2001 to 2013

Elected to lead the Augustinians as their Prior-General in Rome, travelling to its missions around the world, serving two six-year terms

Bishop of Chiclayo

2015 to 2023

He was given a Peruvian passport and used to mend his own motorcar as Bishop of Chiclayo in its stunning Saint Mary’s Cathedral and Prevost still describes it as “my beloved diocese”

Elected Pope

2025

Brought back to Rome and made cardinal, shortlisting bishops for Pope Francis, making him familiar to other cardinals at the conclave in 2025. Prevost prays the Rosary at midday, wears an Apple smartwatch and is the first Pope to send his own emails

CATECHISM: Purity requires modesty, an integral part of temperance. Modesty protects the intimate center of a person, refusing to unveil what should remain hidden. Modesty protects the mystery of love. It encourages patience and moderation in relationships; it keeps silence where there is risk of unhealthy curiosity. It is discreet. Modesty inspires a way of life which makes it possible to resist the allurements of fashion. From one culture to another, modesty exists as an intuition of dignity, the awakening consciousness of being a subject.

Shutterstock © Luca Ponti

Udienza Generale: 13th August 2025

During the Passover supper, Jesus reveals that one of the Twelve is about to betray him. Jesus does not utter the name of Judas. He speaks in a way that each can ask himself the question, one by one, “Surely it is not I?”. Dear friends, this question is among the sincerest we can ask ourselves. It is not the question of the innocent, but the disciple who discovers himself to be fragile. It is not the cry of the guilty, but of him who is aware of being able to do harm. It is in this awareness that the journey of salvation begins.

“

2009

“If we look down to Earth from the heights of heaven,” wrote the Greek pagan Celsus, “would there really be any difference between our activities and those of the ants and bees?” Pope Leo’s first letter to the faithful, Dilexi Te, was originally drafted by his predecessor, just as Pope Francis took-up a paper begun by Pope Benedict XVI: Lumen Fidei, the light of faith, is a monumental meditation on radiance, love and the futility of non-belief. As two poles of the Church, the lofty scholarship of Benedict and the all-spanning forgiveness of Francis lift high the vast tent of human experience, from wandering in Biblical deserts through the lament of philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 to 1778) to the doubts of Dostoyevsky (1821 to 1881) and our present crises of godless individualism.

God is first removed from our everyday lives and put on a different level, consigned to the far beyond. Without his presence, human life is no longer precious and man is cast adrift in nature, renouncing his responsibilities, or assuming the role of a judge, with unlimited power to adjust his surroundings. “Once man has lost the fundamental orientation which unifies his existence, he breaks down into the multiplicity of his desires; in refusing to await the time of promise, his life-story disintegrates into a myriad of unconnected instants.”

Even then, any heart can be easily moved by the beauty and grandeur of life, glimpsing the entire movement of the cosmos towards its fulfilment. Stepping away from our selfish and enclosed egos, we quickly find and recognise Christ, enlarging our lives into a plan infinitely bigger than our own undertakings. And faith is even more than a dialogue between the divine Father and a believing Son. As we draw nearer our Creator, our humanity is not dissolved in the immensity of his light, as a star is engulfed by the dawn, but shines more brightly, like a mirror.

Seeing things as Jesus sees them, with his own eyes, we come to share in Christ’s mind. Perceiving its deepest meaning, we see how God loves the world, constantly guiding it towards himself, encouraging us to live with ever-greater commitment and intensity as we are taken-up in the great pilgrimage of the Church through time, purifying all things, bringing them to their finest expression, assimilating everything it meets. This almost inexpressible communion with the divine reaches “the core of all being, the inmost secret of all reality.”